INTRODUCTION

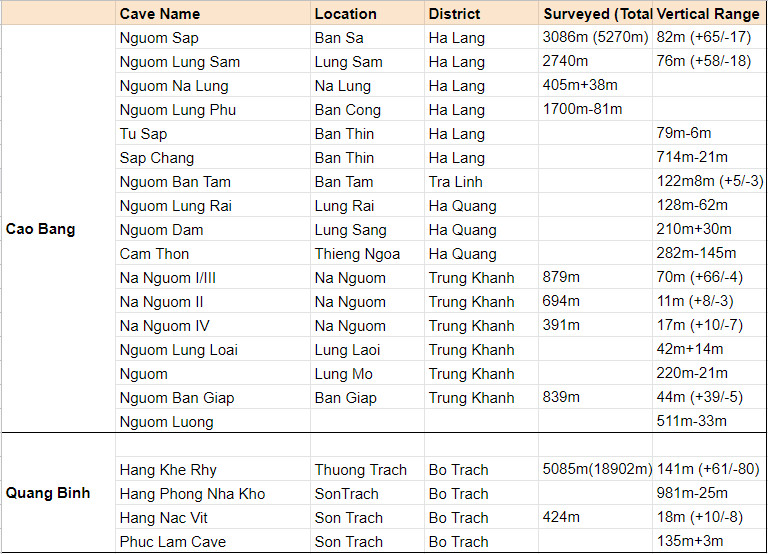

Ten years ago I wrote to Hanoi University asking if they could assist a group of UK cavers in exploring the limestone areas of Vietnam. Since that date we have had a number of successful expeditions to this wonderful country. On all expeditions we have been fortunate to have had with us members from the Geology and Geography Department of the University who have played a full and vital role in all aspects of the expeditions.During the last six expeditions we have explored and surveyed over 140km of magnificent caves in Vietnam. We have concentrated our efforts in 2 main provinces, one in central Vietnam (Quang Binh) and the other in the northeast (Cao Bang). There are many other areas still unchecked but we believe we have been fortunate to be the first to have a major expedition to this fascinating country.

During these expeditions we have made many new friends with people we have come across. We have had many exciting experiences and all have been made more interesting by the kindness and generosity shown by the local people. These people have been through many hardships in the last 50 years and we have found both the young and old to have tremendous resilience to whatever problems are placed in their way. Without their considerable help we would not have been able to have the success that the expeditions have surely achieved.

This latest expedition was no different to many others we have had to Vietnam. The team worked very hard in all aspects of the expedition and free time was an absolute minimum. An important factor in any expedition is how all members can work together in difficult conditions and still have a good time.This was helped considerably by the assistance of Vietnamese members who worked so hard in trying to make our limited stay as easy going as possible.

All the permissions and access problems were sorted out well in advance, making sure of the best possible use of our limited time. Because we were caving in areas very close to sensitive borders it was very important that everything was well organized. At times we were literally a stone’s throw from either China or Laos but because of the correct planning we experienced no problems whatsoever. We had a totally free hand in where we wished to go and all the local people were extremely friendly wherever we went. The biggest problem we encountered was to be dragged into local houses to be offered the local house rice wine before and after caving. However we could cope with such difficulties and the hospitality shown by the people we met was at times quite overwhelming.

The expedition found over 20km of new cave passage. We explored the longest single cave in Vietnam at 18.9km that included a 10.5 km river passage and involved a 4-day underground camp. We have left many caves still unexplored and found a new area with tremendous potential. All members had a wonderful time and the experience of the people of Vietnam is one not to be missed.

This report I hope will explain some of our experiences in this beautiful country and I for one will return to continue our exploration of the amazing caves of Vietnam. The next expedition is scheduled for 2001.

Howard Limbert

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This expedition would not have been possible were it not for the kind support and assistance given by so many people and organisations.Our gratitude to the following:

- The University of Hanoi

- Mr Phan Duy Nga

- Professor Nguyen Quang My

- The People’s committee for Cao Bang Province

- The People’s committee for Quang Binh Province

- The People’s committee for Bo Trach District

- The People’s committee for Ha Lang District

- The People’s committee for Tra Linh District

- The People’s committee for Ha Quang District

- The People’s committee for Trung Khanh District

- The Commandant and Staff Tong Cot frontier

- The committee and residents of Son Trach village

- The Commandant and staff of Ban Ban and Thuong Trach frontier post

- The Commandant and staff of Trung Hoa frontier post

In the UK, we are grateful to the following for sponsorship, equipment, advice and overall assistance.

- David Hood / Ghar Parau Foundation

- The Sports Council for Wales

- Mount Everest Foundation

- Lyon Equipment

- Thai Airways International

- Mr A Eavis

- Mr G Eyre-Morgan

The compilers of this report and the members of the expedition agree that any or all of this report may be copied for the purposes of private research.

TEAM MEMBERS

|

| Cao Bang | Anette Becher | Quang Binh | Anette Becher |

| Martin Holroyd | Martin Holroyd | ||

| Paul Ibberson | Peter Macnab | ||

| Colin Limbert | Colin Limbert | ||

| Debora Limbert | Debora Limbert | ||

| Howard Limbert | Howard Limbert | ||

| Fiona Mackay | Simon Davies | ||

| Steve Milner | Steve Milner | ||

| Mick Nunwick | Mick Nunwick | ||

| Pete O’Neil | Pete O’Neil | ||

| John Palmer | John Palmer | ||

| Geraldine Palmer | Geraldine Palmer | ||

| Nguyen Quang My | Nguyen Quang My | ||

| Troung | Vu Van Phai | ||

| Miss Nhu | Nguyen Hieu |

CAVES EXPLORED DURING 1999

NGUOM SAP

Nguom Sap was originally found during the 1997 expedition on the last day of the trip. It had been explored for 2km with many leads left unexplored. In fact, no passage had been explored to a conclusion so our hopes were high for this cave. The cave is in the Ha Lang district and on the maps the river was seen to be headed into China a significant distance away. The access to this cave is very easy and it is possible to drive within 10 minutes of the entrance. A short walk across paddy fields leads to the entrance where a sizeable stream enters the cave. On our last visit in 1997 a much larger stream was present but this year much of Vietnam like many parts of Asia was experiencing a drought. The team split up into 3 groups all armed with survey gear and a copy of the survey to check out leads from the previous trip. The aim was to explore, survey and photograph as much as possible in the time available. Nguom Sap is an excellent cave with many levels of development; hence the potential was quite good for a significant system to be found.Following the stream from the entrance, a lake is reached (Hippo Crossing) and wading to the right soon leads to dry passage. The water sinks somewhere in the lake and the only other place it is seen again is to follow a passage back over the lake, which has a good draught for 200m to a short drop with the sound of water below. This was the limit of 1997 exploration and one team came armed with equipment to drop this hole. Pete ‘Grabber’ O Neill hurriedly attached a ladder and descended to the water. The sound of running water was very inviting, however the passage quickly sumped and one of our most hopeful leads was finished.Over the top of the pitch a passage continued so the rest of the team left Pete to detackle whilst they surveyed a passage which was getting larger all the time. After a couple of hundred metres the passage led into a huge chamber “Champagne Supernova” with what looked a number of passages radiating out. One passage in particular is spectacularly decorated and the huge curtains that cover the right hand wall are a tremendous sight. This gour filled passage was again grabbed by the notorious team member who had no sooner got himself to the front before it quickly choked.While the rest of the team was painstakingly surveying this large chamber an obvious passage was seen at the top of the boulder slope and Grabber decided he had better try that. The survey team made their way towards the passage only to be greeted by a dejected Pete with the words ‘choked’ again ringing around the chamber. At this point it was decided to give Pete the instruments due to the fact he was becoming a Jonah and this should stop him sneakily grabbing any future passage.Back at Hippo Crossing the flood overflow passage is followed downstream “Waltzing Along” passing a number of side passages which were checked out and quickly finished. About 1km into the cave the passage turns to the left and a high level can be entered on the right. In 1997 the lower passage was surveyed to the start of a swim. However because of the drought in Vietnam the swim no longer existed and the team clad in wet suits were able to walk through this open passage. The walking passage continued to a large breakdown chamber ”Destiny Calling”. Bending to the right the passage continued, reaching another area of breakdown. After this some pools were reached which could be waded through. The passage became smaller with a lot of decorations. The way on was up through the formations and then a drop to the stream led to a swim and finally a sump after 870m.

The team split up into 3 groups all armed with survey gear and a copy of the survey to check out leads from the previous trip. The aim was to explore, survey and photograph as much as possible in the time available. Nguom Sap is an excellent cave with many levels of development; hence the potential was quite good for a significant system to be found.Following the stream from the entrance, a lake is reached (Hippo Crossing) and wading to the right soon leads to dry passage. The water sinks somewhere in the lake and the only other place it is seen again is to follow a passage back over the lake, which has a good draught for 200m to a short drop with the sound of water below. This was the limit of 1997 exploration and one team came armed with equipment to drop this hole. Pete ‘Grabber’ O Neill hurriedly attached a ladder and descended to the water. The sound of running water was very inviting, however the passage quickly sumped and one of our most hopeful leads was finished.Over the top of the pitch a passage continued so the rest of the team left Pete to detackle whilst they surveyed a passage which was getting larger all the time. After a couple of hundred metres the passage led into a huge chamber “Champagne Supernova” with what looked a number of passages radiating out. One passage in particular is spectacularly decorated and the huge curtains that cover the right hand wall are a tremendous sight. This gour filled passage was again grabbed by the notorious team member who had no sooner got himself to the front before it quickly choked.While the rest of the team was painstakingly surveying this large chamber an obvious passage was seen at the top of the boulder slope and Grabber decided he had better try that. The survey team made their way towards the passage only to be greeted by a dejected Pete with the words ‘choked’ again ringing around the chamber. At this point it was decided to give Pete the instruments due to the fact he was becoming a Jonah and this should stop him sneakily grabbing any future passage.Back at Hippo Crossing the flood overflow passage is followed downstream “Waltzing Along” passing a number of side passages which were checked out and quickly finished. About 1km into the cave the passage turns to the left and a high level can be entered on the right. In 1997 the lower passage was surveyed to the start of a swim. However because of the drought in Vietnam the swim no longer existed and the team clad in wet suits were able to walk through this open passage. The walking passage continued to a large breakdown chamber ”Destiny Calling”. Bending to the right the passage continued, reaching another area of breakdown. After this some pools were reached which could be waded through. The passage became smaller with a lot of decorations. The way on was up through the formations and then a drop to the stream led to a swim and finally a sump after 870m.

Continuing along the high level passage, ”Wembley Calling” is reached, an area the size of a football pitch and amazingly flat. From here a number of leads were present and all were checked out. Two small side passages had previously ended at low muddy pools. The left-hand passage connected back to a small passage the other side of “ Wembley Calling”. The right hand passage connected to the main passage before the junction. Both pools had dried up, although the passages were both very muddy.

Two leads around the well-decorated chamber were surveyed. One ended quickly in a pitch to a choke. The other led to 250m of well decorated high level passage ending in a calcite choke.

The end point of 1997 “Wonderwall” however proved very interesting. The right hand passage led to a short drop of 5 metres to a muddy continuation. We quickly slid down this thinking it may be interesting on the return but with no tackle we had little choice. We continued surveying in a passage of 10m by 4m which divided and the right hand branch soon led to a boulder choke with a strong draught coming out but no way through.The main passage “Acquiesce” continued again to a boulder choke, which despite the draught no way on was found. However we had surveyed 405m.

The end point of 1997 “Wonderwall” however proved very interesting. The right hand passage led to a short drop of 5 metres to a muddy continuation. We quickly slid down this thinking it may be interesting on the return but with no tackle we had little choice. We continued surveying in a passage of 10m by 4m which divided and the right hand branch soon led to a boulder choke with a strong draught coming out but no way through.The main passage “Acquiesce” continued again to a boulder choke, which despite the draught no way on was found. However we had surveyed 405m.

The climb proved a little tricky on the return. The mud and steepness of the slope was proving a real obstacle. By making a pyramid of people one member was able to claw his way to the top. Then using the survey tape, which was surprisingly strong, all the other members were able to just climb up back into the main passage “Wonderwall”. On this team was a Vietnamese member from the University who was on her first trip underground. I do not think she was too impressed with our improvisation and was very pleased to reach the top of the climb.

Back in the main passage the now overheated team explored the left-hand branch. Following the very large passage up and over a boulder slope led back down to a large passage “Headshrinker” containing a small stream. The decorations in this area of the cave are quite spectacular and many huge columns and gours are seen. This passage was followed for 440m to a draughting climb. This was climbed to the surface to emerge in an enclosed doline with a river in the bottom, which could be seen leading to a large cliff face. This was left for another day whilst other leads were checked out in Nguom Sap.

Before we exited the cave we managed to photograph some of the pretty parts of the cave. The team all left the cave just before dark, in time to get back to our transport after a very successful trip.

Nguom Sap was surveyed for a total of 5270m with a vertical development of 82m. This is the longest cave in Cao Bang province and because of the continuing leads across the next doline we hoped it would prove just a small part of a larger system.Due to the many levels of development a lot of cave was explored in quite a small section of the limestone massif.

Nguom Sap was surveyed for a total of 5270m with a vertical development of 82m. This is the longest cave in Cao Bang province and because of the continuing leads across the next doline we hoped it would prove just a small part of a larger system.Due to the many levels of development a lot of cave was explored in quite a small section of the limestone massif.

This spectacular cave was a great start to our caving in Cao Bang province and gave us much hope of future discoveries in this beautiful area of Vietnam .

Howard Limbert.

NGUOM LUNG SAM

12th March 1999

After yesterday’s success in Nguom Sap Mick, Howard, Steve and myself accompanied by Miss Nhu and a local guide, walked over a col to the village of Lung Sam, in search of the continuation of Nguom Sap.The area map clearly showed the Nguom Sap waterresurging and then sinking again in the Lung Sam doline.Reaching the top of the col we could clearly see a massive cave entrance, with a large river rising to the left and sinking in the cave entrance.The pace quickened as we neared the entrance, it looked a dead cert.The entrance was approximately 45 metres wide by 40 metres high, we descended a steep slope of breakdown to reach the river, which emerged from a sumped side and spewed forth across a large shingle floor.Excitedly, wedonned wetsuits and surveyed in.After several hundred metres the stream shot off to the right in a 4 by 4 metre passage for 40 metres to a sump, the continuing main passage was high and slightly inclined.To the left were several ramps up to a massive high level fossil passage, which meandered around the continuing lower streamway for most of the cave.

The stream now did a sharp right turn, behind a large block at the start of the ’Master Plan.’Steve, our team fish, set off across a swim in a 5 metre wide by 20 metre high passage and we all followed like sheep. Later we discovered this section was just a wade.Beyond the swim, to the right a short passage discharged the main stream from a sump.Continuing downstream was easy walking on a shingle floor, the high level passage could be seen crossing some 15 metres above.We then came to an area of calcited breakdown, the passage above was massive but unreachable.The way on was a drop down between calcite flows to a low roofed swim called ‘the Canal.’

After 100 metres the canal again rejoined the upper fossil passage and dimensions of 12 metres by 30 metres followed, with fast flowing cascades and short swims.At a prominent corner we decided to call it a day and return to the high level passages near the entrance.

Climbing up the 40 metres slope we entered the 40 metre by 15 metre high ‘Roll with it’ passage.The floor was level, sandy and largely free of breakdown, so we wandered along doing 50 metre survey legs with silly grins.In the downstream direction we reached a pitch back down to stream level.However upstream the dimensions grew smaller until a large ramp down led back again to stream level near the entrance.

Climbing up the 40 metres slope we entered the 40 metre by 15 metre high ‘Roll with it’ passage.The floor was level, sandy and largely free of breakdown, so we wandered along doing 50 metre survey legs with silly grins.In the downstream direction we reached a pitch back down to stream level.However upstream the dimensions grew smaller until a large ramp down led back again to stream level near the entrance.

Back at the entrance, it was smiles all round.We’d surveyed 1.3km of superb passage and we just knew tomorrow’s return was not to be missed.

13th March 1999

Today’s plan was for Mick, Martin and myself to travel to yesterday’s last survey station.We were granted ½ hour of passage grabbing before marking a spot as the start of our surveying.

The second team of Howard, Fiona, Anette and Steve were to follow photographing and upon reaching yesterday’s last survey leg, they were to survey our ½ hour of grabbed passage.

Team Grab set off, quickly reaching yesterday’s last station.We then covered ½ hour of very sporting passages, with many cascades and short swims in passage generally 8 metres wide by 15 metres high.We started surveying in an area of fast flowing water, just before a 3 metre climb down.At the bottom the current swept us on, eventually the high level fossil passage dropped down and merged with the active level and the passage dimensions became a staggering 100 metres wide by 60 – 70 metres high.

The ‘Ha Lang Highway’ was truly awesome, the sort of passage we’d travelled to Vietnam to find.Huge stal columns adorned the passage, some fallen like massive tree trunks, and the stream was lost beneath the expanse of the boulder floor.As we surveyed another entrance came into view, possibly 400 metres away.We carried on past the steep ramp up to daylight, onto a second entrance where we surveyed out into the dense jungle of a doline.Stumbling round in the heat of the day clad in wetsuits was very unpleasant, with much relief we found a 3rd entrance back into the cave.It became obvious that the cave passage merely skirted the edge of the doline.We also noticed evidence of wood cutters, there must be a cut route overground to this point.

Underground the continuation was down some steep climbs to stream level, where the water deepened and we had to swim.After several hundred metres it become obvious that a sump was inevitable as the walls were dark and sombre.Leaving myself stranded on a rock island , Mick and Martin surveyed two more out of depth legs before calling it the end.Mick could be heard shouting “for f***s sake” as he repeatedly got caught up in the survey tape and the drag cord of his floating tackle sack, whilst trying to swim.

We returned to the ‘Ha Lang Highway’ for some food and then checked out some side passages before heading off out.We caught up with Howard’s team near the entrance, they’d completed their section of survey as well as taking a good photographic record of the first half of the cave.Unfortunately time restraints didn’t allow us a return.

We returned to the ‘Ha Lang Highway’ for some food and then checked out some side passages before heading off out.We caught up with Howard’s team near the entrance, they’d completed their section of survey as well as taking a good photographic record of the first half of the cave.Unfortunately time restraints didn’t allow us a return.

Nguom Lung Sam was a stunning cave to explore. The surveying length was 2.7km and certainly for 3 members of the expedition, one of the best days exploration of the trip.The area map shows the Nguom Lung Sam River rising in a further doline, before sinking again and travelling under the Chinese border.The search for this continuation should be a must for the next expedition.

Peter O’Neil

NGUOM LUNG PHU

A team returned to Nguom Han, a cave we had connected to Nguom Pac Bo in 1997. Due to lack of time we had not investigated the left-hand passage just inside the entrance. This passage was found to be the downstream continuation of the stream which surfaces nearby and flows overland to sink into Nguom Pac Bo. The passage sumped very quickly.

The team continued to the west over a small col, where local woodcutters led us to an entrance. A small slot at the base of a cliff was found to emit a very strong warm draught. Not knowing what to make of this warm air, we descended the entrance pitch of 8m. The cave continued as a straight tall rift for about 30m to another pitch. This looked to be about 10m, but the bottom could not be seen. The falling rock test revealed it to be further than 10m. Insufficient tackle meant we would have to return the next day.

Another entrance about 50m above Nguom Lung Phu was investigated. Although a huge entrance ( 80m wide x 40m high ) the whole area was completely calcited and no passage could be found.

Returning the next day, the next section of pitches was descended. Several rebelays later the 24m pitch was bottomed landing in a large chamber. One side of the chamber led to a calcite choke, the other to a large collapse area. Carefully descending the steep slippery slope we entered a lower passage. To the west a short length of passage led to another pitch with the sound of running water below. Heading east the passage continued, a strong draught (cooler now) encouraging us. The passage floor contained large old gours, which had been covered over by a thick deposit of mud. A junction was reached with a small side passage. A quick recce and “ we want to be going this way !” As usual the promise of a streamway takes priority.

A 5m climb rigged for safety dropped us into the middle of a stream passage. Knowing the biggest potential was upstream, we set off surveying only to be shortly disappointed by a sump and calcite choke. Downstream the passage continued in fine style, although not necessitating the wetsuits we had immediately donned. Easy walking with some boulder sections made the surveying pleasant.

A large dry passage on the right was quickly checked and it’s occupant, a large green and red snake, woken up. Leaving this passage for later we continued downstream finally reaching our first swim. The draught at this point was extremely strong and very cold, the exit soon visible. Climbing up we realised we were very close to Nguom Han entrance, in a shaft which in fact was crossed by the footpath via a rock bridge. Continuing downstream, the passage soon closed down to a very low crawl, which must be within metres of Nguom Han.

Returning to Snake Inlet we surveyed cautiously and soon found our friend. We snapped a few photos and surveyed past. The passage, very well decorated, continued for 160m to a pitch into a lower passage with a large flowstone opposite. Clearly a passage we had not yet visited.

The next day we returned to descend the pitch into the upstream section of the streamway. The pitch turned out to be 13m and landed perfectly on a gravel bank surrounded by water. A quick check showed we would soon get very wet so we changed into wetsuits and started the survey. Disappointingly another sump was reached after 66m. The calcite flowstone in front was climbed but soon choked. There appears to be a much higher level, which may bypass the sump, but would require bolting. The sump was named Missing Metres. Downstream of the pitch we surveyed about 30m to a sump and calcite flow, very close to our upstream sump of the previous day.

Changing back into dry gear we de-rigged the pitch and returned to the dry passage we had abandoned previously in favour of the streamway. Kidney Stone Bypass is a lovely dry passage, very well decorated. Soon we arrived at a large flowstone and could look up into Snake Inlet. Luckily the passage continued below and we connected it through to the streamway at a junction just downstream of Snake Inlet.

Lung Phu is 1.7km long and 81m deep. The length of the streamway Ban Cong Freeway was 600m. There is potential for 2 to 3km of cave from the upstream sump to the sinks marked on the map. The next trip will attempt to find a way in from the sinks.

Debora Limbert

NGUOM NA LUNG

This was a resurgence cave previously visited by Paul and John on the ‘97 expedition. On this visit a large river was issuing from the boulders, but lack of equipment and time meant the cave remained unexplored. Paul referred to it as unfinished business and was keen to return with a team happy in water! Having been before Paul and our driver were able to find the parking spot with little difficulty and thus we had no English speaking Vietnamese with us .

From a col above the village of Canh Nghieu a path gently descends into the valley below until a bridge crosses the resurging river, on this visit the resurgence was dry, making the wetsuits seem an overkill. No obvious way on could be found on an initial look.Martin headed off up the hillside above to look for another entrance leaving the others in the choke. 100 metres above, Martin located a large entrance shaft with a passage below.With some trepidation he freeclimbed down an exposed route into the cave.A downstream passage led back to the resurgence whilst the upstream passage led to a featureless 5 metre climb with a larger passage above.Happy that the entrance choke could now be by-passed a return was made.Meanwhile Anette had forced a way through the choke dropping into a narrow streamway.Anette’s route was unanimously chosen on hearing of the exposed shaft.

The way through involved a climb through boulders on the right-hand side of the entrance dropping back down into the river.An easy stretch of river passage was followed to the base of the shaft previously descended by Martin.The upstream climb thwarted all attempts to scale it.The only way on involved a difficult route at stream level to a boulder choke.The team split up to look for a way on, confident a large passage must exist above. Martin and Paul climbed up high and simultaneously popped their heads into a vast passage.The way on was of impressive proportions and the 50 metre legs followed.Unfortunately our glee was short lived as the passage dropped steeply down to stream level with a narrow canal leading off.After a combination of swimming and climbs over sumped sections a terminal looking sump was reached.Martin made an awkward climb up into the rift above, stopping at the start of an exposed traverse with silt covered walls.Beyond the passage looked to be opening out into something bigger, but without equipment the temptation was resisted.

On our return to the jeep, two stern faced soldiers greeted us with a request to see our permits and passports, both of which were back at base.We were then asked to accompany the soldiers to their camp on the Chinese border.The next hour was spent entertaining a village drunk or so we thought until we were taken into a building.We were then joined by our ‘drunk’ dressed in military uniform and obviously the camp commander.After insisting Martin took up smoking and Anette was his wife the Commander interviewed us and our driver who obviously did the business as after another hour and numerous cups of green tea we were free!What another great Vietnam caving experience!

Martin Holroyd

TU SAP & SAP CHANG

Prior to leaving Ha Lang a small team, Martin, Anette, Steve and I went to cross off a few likely looking areas on the map. The first to be looked at wasthe source of the main Ha Lang River.After a few missed turns in the jeep we managed to persuade a woman and her small child to come with us and give up working in the fields for the day. Through the normal communication difficulties and asking for the source of the river we came to a small rocky outcrop in the middle of a ploughed field. This we were assured was where all the water came from although it was completely dry with no discernible entrance. We decided to move on and look at some more possibilities. A long walk looked likely over the next couple of cols.Unsure of what we would find and whether it had been looked at before, a small amount of dissent was apparent.

On the walk over we picked up a few followers and arrived in a small village. This area had a lot more water and was already planting rice whereas Ha Lang was still very dry. Following the riverbed we came to a couple of entrances and decided to look at the larger one first. We were told that this didn’t go anywhere and we ought to look at the other as it went through the hill. For completeness the first had to be looked at but it choked very quickly with huge tree trunks and other assorted vegetation. This meant that the other should take us through the hill.

The cave was a small dry stream passage with some decorations, obviously an overspill from the main choked drain. After a very smelly descent through what would be a sump in wet weather we did surface into another a valley. Time being short we didn’t venture further to look for more entrances but returned to our interpreter and the trudge back over the cols. After discovering a very pleasant 700m through trip the walk wasn’t as bad as first expected!

Fiona Mackay

TRA LINH – THE ARCH GRABBERS’ STORY

On our first afternoon in Tra Linh prior to moving “up the hill” to the plateau above the resurgences visited in 1997, a team set out to visit some interesting sites noted close to the Cao Bang to Tra Linh road at Quang Dau. Splitting into two teams, half were despatched to an obvious sink at Nguom Sua whilst the remainder headed upstream to investigate a probable resurgence cave.

The sink team found a heavily silted choke and little else, but were rewarded with a pleasant walk through some of the most stunningly beautiful scenery we have come across even given that Cao Bang is an outstandingly scenic province.

The upstream team of Paul, Steve and “Grabber” O’Neill had a little more success. The water did in fact emerge from a cave at the head of the valley, but only a short swim lay between the entrance and the sump – scant reward for Steve’s bold effort in headtorch and underpants! At least the sight proved amusing to the locals who accompanied us to the entrance. In wet weather, this would no doubt be an impressive site as the far side of the ridge contains the sink for much of the water in the Tra Linh valley.

Heading back downstream, we noted a possible entrance a little way up the valley side. Whilst Pete and Paul set off to investigate, Steve was drawn to an altogether more impressive spot – a perfect karst cone at the head of the valley had at some time in the distant past been intersected by a huge fossil passage. With the erosion of the surrounding area, this passage now manifested itself as a giant eyehole in the cone. It might well be called the F*** M* Eyehole as this was the expression of everyone as they first saw the sight from the head of the valley. In Steve’s eyes, it was a passage worth visiting.

Back at the lesser entrance, we had noted a decent draught and a dry walking size passage. We returned to daylight to call over Steve with the survey gear, only to hear a distant rustling, grunting and the rumble of loose rocks from somewhere halfway up the cliff below the eyehole. Clearly he was otherwise engaged, so we decided to check out the cave a bit further.

With one very used carbide (Pete) and a glow-worm headtorch (Paul), progress was not rapid, especially as a couple of calcite ramps and climbs made us a little wary. A traverse around a pit with a murky-looking pool initially stopped the lone Grabber, but with glow-worm backup, he was ready to have a go. We decided that as time was getting on and as we had no survey gear it would be best to check the passage continued and return the following day to complete the job properly.

Once across the traverse, Pete dropped into a continuation of the main passage – large, walking and wide open! With the immortal line “I’m sorry Paul, I can’t control myself!” the “leave it until tomorrow” plan was aborted and more metres were grabbed, unfortunately sufficient metres to reach the exit on the far side of the ridge.

On returning to the traverse, Pete estimated some 200-300m to the exit. This would give us perhaps 500-600m in total and we agreed that we would return to survey the next day.

Unfortunately, the following day we moved en masse to Tong Cot to begin exploration on the plateau and did not manage to return to finish what we had started. A thoroughly reprehensible situation which just goes to emphasise the importance of surveying as you go. So really we explored half a kilometre more than the records show, but we know we can’t claim it. At least the next expedition can already count on 500m or so of survey before any serious searching begins! And most of all, whoever takes on the left-over duty of the 1999 expedition (and we definitely will if we are around) is assured of a gentle stroll through some amazing countryside and a few easy metres of survey courtesy of the Arch Grabbers. Oh, and for future reference, a hot, dirty and bleeding Mr. Milner was of the opinion that the view from the eyehole was more than adequate compensation for negotiating the vertical jungle and loose rock.

Paul Ibberson

CAM THON

During the 1997 expedition, we had visited an area of Ha Quang districtin the vicinity of the main road through to Pac Bo. This allowed us relatively easy access to a number of potentially very interesting sites. Only one of these locations yielded any surveyed cave, but at both Pac Bo and Na Giang, major resurgences were noted. Although no dry cave existed, the volume of water issuing from the base of the massif gave us hope that somewhere in the range of hills to the north we might just find the way into another superb Vietnamese cave system.

Two years later we arrived at the border post above the village of Tong Cot. With a larger team than in 1997 and the whole of 30km by 10km plateau to be investigated, we had high hopes. The major problem we had at the time was that the area was suffering a severe water shortage. Tankers were being used by the Vietnamese to bring water to the villages perched high on this arid plateau and the people had more important concerns than answering silly questions from a load of westerners about holes in the ground ! However, as always in Vietnam, we were made more than welcome by the locals and they viewed our strange fascinations with a kind of quizzical amusement.

Having driven up the long valley from Tra Linh in the morning, Team Grab decided that an obvious hole was the most promising lead and headed off to scoop some passage. Deb took another group to check out some leads back down the valley which we had been told about in 1997. This left Howard, Martin, Fiona and myself to set off uphill onto the plateau proper. Being slightly less impulsive than some (and not fancying a fruitless trudge in the heat of the day), we first asked some of the locals where the caves were to be found. Very soon we had a guide and were on our way up the road on foot. After about 1km, amidst mutterings regarding the eminent suitability of the track for our jeeps, a major paddy from the expedition leader was averted as our guide took a left turn onto a rough single-person trail.

About half an hour later, we reached a col above the village of Thieng Ngoa and took a well earned breather. To the north and east lay the tower karst of China and to the south and west, the Ha Quang massif. A truly spectacular resting point and a clear indication of the potential of the area.

Just below the col, our destination; an obvious doline with a cave entrance at its lower end. A quick look revealed a vadose canyon with a floor of dry cobbles. It could almost have been the Dales, were it not for the fact that we were in T shirts and standing up in a passage at least a metre wide. 100m was quickly surveyed to the head of a PITCH. On this occasion we had no rope, so a return was immediately planned for the following day.

Although we had expected some vertical development, logistical factors had dictated that we could only manage to get about 200m of rope to Tong Cot. This was duly stuffed into tackle bags and carted up the hill. The team’s composition for the up and down bits was slightly different, with Howard and Fiona being replaced by Steve and John.

The first pitch was swiftly descended, landing on a ledge above a further drop. Handy naturals made rigging an easy task. Another short drop followed in the canyon, before a rub point forced the application of the bolt kit for the last 14m section. Beyond this, naturals gave good hangs for two more pitches to a hading rift. Still on the rope, the rift opened onto a larger section and finally a flat bit. This cave was turning out to be a little different from the norm.

The horizontal section went on for at least 35m until another pitch blocked our progress. It sounded big. Our last rope was 45m of 8mm. I placed one bolt and then tactically smacked my thumb with the hammer. Big Nose took over bolting and having completed the rigging felt obliged to make the first descent. Knowing there was a good chance of dangling at the end of a bit of 8mm over a big hole, I reluctantly had to concede the honour.

The rope did make it as far as a ledge about 30m down the shaft, but was not quite long enough to reach the bottom, wherever that may be…

Once the numbers were crunched, we found Cam Thon to be 282m long and 145m deep to the ledge. Not exactly a world beater, but with the likely resurgence 10km to the south and around 800m lower, this cave will be a major objective for the next expedition. More rope has already been ordered.

Paul Ibberson

TRUNG KHANH – NA NGUOM SYSTEM

As every morning at the Tong Cot boundary station, the 5:45 a.m. clank reveille (a pair of pliers erratically pounded into a suspended lorry wheel) wakes us rather earlier than hoped for. With daylight about to break, we peer through the dusty windows to find a handful of young soldiers in shorts, vests, and plastic sandals going through their morning gymnastics, driven by whistles and shouts. We hastily throw our belongings into the jeeps. I am glad to leave Tong Cot boundary station to get on with its military routine and football games. It is going to be a fair drive to the next stop-over point.

Trung Khanh provides the first inkling of things to come.Here, the familiar palaearctic fauna and flora of the higher altitudes begins to give way to wildlife more commonly associated with the tropics. The magpies, great tits and collared crows of northern Cao Bang become scarcer as we drive on, the vegetation infinitely denser and verdant, the air heavy with humidity and enigmatic scents. Giant clumps of bamboo hunker alongside the river banks, tethered horses feed on lush green fields, and water buffaloes wallow in festering mud holes. While waiting to introduce ourselves to the People’s Committee of Trung Khanh, I discover a massive atlas moth resting under the building’s concrete balcony. At last, an insect so large it is difficult to hold! Later, I spot hundreds of giant carpenter bees foraging among the honey scented trees, and then I find a huge moth cocoon. From now walking to the caves will be as exciting as the caving itself.

The vibrant town of Trung Khanh holds a busy market the day we arrive. The only puzzling feature of the town is its loudspeaker system showering the town with Vietnamese music, interspersed with what we assume is propaganda, from dawn until dusk. Fascinating for the first couple of hours, but I cannot imagine that tourists will appreciate this in the long term.

Howard has pointed out a sizeable river that seemingly emerges from the end of a valley, a few miles away. Our aim is to explore the resurgence. Despite the predictable argument with our drivers, weary of having to drive us from cave to cave without a day’s rest, and reluctant to scrape their polished jeeps along ruts in dusty country tracks, we manage to get relatively close to our presumed resurgence. The walk there proceeds along small ridges that frame the ubiquitous rice paddies, into a broad valley with hills rising up both sides. The river is instantly apparent and we keep to its banks, crossing when necessary.

Mick peers into the resurgence and finds it flowing sluggishly through a very deep layer of liquid mud. There is a phenomenal draught. Nobody has the equipment required for a swimming survey in a deep water cave and, after some discussion, Paul, Fiona and I leave to investigate a hole in the hill directly opposite the resurgence, while the others explore a hole above the resurgence, later known as Na Nguom III. We plan to leave the actual resurgence for tomorrow.

NA NGUOM II

Paul and Fiona have already started surveying when I finally arrive. The cave entrance is about 5 meters wide and 3 meters high and leads into a roomy chamber with three ways on. We leave the smaller passages for the return and go for the one leading most obviously into the hillside. The cave is essentially dry in that there is no flowing streamway, but in places large dripwater pools have to be crossed. The first pool is quickly circumnavigated and followed by a beautifully decorated flowstone wall. A climb up on the right hand side leads to a higher level passage – the way on. This narrow passage is decorated with sharp white crystals and draughts furiously. After a flat out squeeze, the passage eventually widens to reveal a 5m long knee-deep drip pool. I am wearing my only pair of dry boots and am determined they should remain so for the rest of this trip. Fortunately, there is a slippery shelf with a few stalagmites that allows us to traverse the pool and me to keep my precious boots dry. It is obvious that people have been here before. The ledge we have just traversed looks worn and there are occasional footprints in the mud.

The cave continues nearly in a straight line north, then meanders in a north-west, north-east direction with an overall north-west trend. Much of the cave is beautifully decorated with gour pools and stal and columns. Surveying is easy, mostly walking and dodging formations, and eventually we reach what looks like a giant flowstone choke. We squeeze through a small passage at the right hand edge of the flowstone, but this only connects back into the passage. Itmay be possible to aid-climb the smooth stone to get over the top. An alternative way on is a steep-sided 3m deep muddy rift that goes off into the distance on the right hand wall. We have no climbing gear and therefore return to a fork in the passage further back. After a short distance, the roof of this passage lowers down to a flat out crawl. I think I can see a solid mud flat with a black space behind, but for some reason Fiona and Paul do not seem too keen to explore this lead. Feeling heroic for once, I slide under the roof onto the mud floor, feet first. I am nearly through when my feet mysteriously lose their grip and, amidst a lot of guffawing from Paul and Fiona, I slide feet first to land on my bottom in an ankle deep crystal-clear pool. So much for my dry boots.

On the way back I am in a slight huff. Nonetheless, we remember to check the two remaining ways on in the entrance chamber. They become tight soon, but continue in the direction of the way out.

NA NGUOM I+III

Mick has worked out an easier way to the caves, approaching the valley from the near end. This does not only make for a more straight-forward walk, but also avoids the inevitable attempt at mutiny on the drivers’ side. We pass between the steep karst towers framing the valley, back-lit by the morning sun and softened by the ever-present haze. The lush, grassy river bank provides the perfect kitting-up site. Originally we meant to leapfrog, but we discover that one team have left their survey tape in the jeep, meaning we end up as a somewhat overpowered fivesome.

I know that it is going to be hip-deep mud, but nevertheless am surprised by what comes next. Martin strides off powerfully, wellies on head. After a few steps the name of the passage suggests itself from Martin’s repeatedly expressed disgust (For F…. Sake!) with the state of this streamway. Initially, I find this mud is quite a lark. After a few steps, however, I run out of momentum and begin to sink deeper and deeper with every move designed to pull my legs out. Eventually, the glutinous mud closes around my hips with a lip-smacking sound. Everyone else seems miles ahead, and panic rises. Meanwhile the few onlookers from the village giggle at my feeble attempts to keep up. Surely, they are not going to leave me here to be swallowed by the resurgence. Hearing my pathetic calls for help, Mick and Steve eventually come to my rescue. I proceed in the middle of the stream, where I manage to make forward progress with relative ease, adopting a floating-wallow style.

After about fifteen meters, we reach a low arch. This has got to be a duck or sump in high water conditions. Here, the draught howls with such strength that it blows out my carbide light. Shortly after, a muddy chamber appears. Turning left, we climb a small sediment dam, over which the streamway idly trickles. We then cross two short canals. At this point, the low, muddy aspect of the cave gives way to clean-washed limestone, and the cave becomes lofty and quite pretty. We swim through emerald-green water along the third deep canal and climb up a miniature waterfall into a section partly constricted by white stalbosses. The streamway flows merrily. A further swim produces what at first seems a dead end. Mick climbs out of the water, up several crumbly boulders, and then scales a giant flowstone that towers above us hinting at a large, black space beyond. The way on. John and Martin more or less push me up this steep climb with additional help from my wetsuit, which sticks to the crystal-covered formations like Velcro.

More swimming, followed by wading over soft, popcorn-encrusted gour pools. For the second time, there is no apparent way on. Eventually, we notice a very low duck in the sump pool. Martin takes a deep breath and ducks under – thumbs up! We follow, one by one, to find yet more lofty passage, this time surrounded by substantial muddy banks. The river is wider and much shallower here. We carry on walking along the meandering streamway, past the mud banks into the next part of this tall passage. Beyond a shallow pool – another sump. We refuse to give up. Mick and Martin begin to climb the surrounding flowstone. One area looks particularly promising, and it seems that the draught might go up along it. Opinions are divided as to whether the black space we can just about infer beyond the flowstone wall is the way on, or merely forms part of the fossil meander we have already seen. There is only one way to find out: John and Mick return to the entrance to collect a 20m rope which will be used to belay the climber. Martin volunteers for this task. Nearly two hours and several dodgy belays later, Martin is confident that there is no easy way on here. This does not mean there is not a higher level passage to bypass this sump, but if we are to get to Cao Bang this evening, we need to call it a day.

Outside the resurgence, the entire village has congregated. Forgetting the waterbuffaloes they are supposed to be minding, the villagers come over to inspect our wetsuits and other gear. They grin at our white skin, pull the hair on our arms and generally make friendly contact, while the water buffaloes blissfully chomp their way through the crops.

Anette Becher

LUNG MO AND NA NGUOM IV

On the morning of the last day in Trung Khanh, Colin, Pete and Paul headed out to check out a cave recommended to us by the President. Only a few kilometres outside the town, our jeep pulled over and fingers were pointed in the direction of a nearby hill. A nice steady walk, or so we thought.

Picking up a local guide, we set off up and around the hillside. As we climbed higher and higher, it became apparent that the prospects for major horizontal development were diminishing rapidly as we neared the top of the ridge. Imagine our surprise when we eventually reached a slope down into the sort of large entrance chamber that has no right to be this high up on a hilltop.

A rift to one side led on into a 20m diameter trunk passage which bored off into the distance. The locals followed with their glow-worm torches as we surveyed in. A calcite blockage provided the only obstacle – a climb up and over – before the tunnel closed down. A climb up and through boulders gave access to a second entrance and a view back over the lower part of the valley.

With 220m of survey under our belts and most of the day remaining, we headed back to meet the jeep and continue to the Na Nguom area.

Back near the site of the previous day’s explorations, we set about investigating an obvious entrance on the hillside to the west of Na Nguom I + III. This was easily gained after a quick scramble up the slope and a climb down into a chamber.

The way on started small, but following a couple of switchbacks emerged in another pleasant tunnel. The metres were quickly clocked up as we headed south east under the hill. This was clearly trending in a similar direction to Na Nguom I and offered the potential of a link between the various entrances.

Around 250m in, the passage closed down to a choke, but the draught had disappeared into the roof. Pete set about finding where it had gone. Some bold and circuitous climbing later, he reported a way on. We followed the exposed climb and soon found ourselves way above the blockage. A climb down led into an area of low, muddy tubes which looked none too promising, but Pete was quickly off again in search of the elusive draught.

Climbing high into the roof, he once more declared that the way on had been found. We had a brief consultation and with time pressing decided that if we were to make Cao Bang before nightfall, we had better call it a day. When the survey was drawn up, it became clear that the fourth entrance was indeed heading towards the other parts of the system and a little more time would probably have seen them connected. In addition to this, it is still a fair way to the presumed sink for the Na Nguom I streamway. As with many areas in Cao Bang, there is still the prospect of plenty more cave to be explored.

Paul Ibberson

NGUOM BAN GIAP

Imagine standing admiring a beautiful waterfall, a man ploughing a field with his water buffalo in the foreground, trying to work out if it will ever look anything like as spectacular in a photograph when a massive explosion disturbs your peaceful contemplation. Well this is where we found ourselves on the last but one day of caving in Cao Bang. We had gone to take photographs ( if necessary) of a show cave Howard and Deb had discovered in 1995 and to explore further caves that had been talked about on their last visit. The starting point though was a spot of tourism andphoto taking of Ban Zioc waterfalls, a huge waterfall in flood and still pretty impressive in the dry season. The waterfalls are on the border between China and Vietnam and an expanding tourist attraction for the Chinese and Vietnamese so major road works were taking place to improve the road from Trung Khanh to Ban Zioc. This involved blasting large lumps of rock into small lumps of rock and then hammering them into even smaller lumps of rock right above the waterfall.

The army guide we had with us told of a cave he knewbelow the road(which was currently being built). After donning regulation caving gear – shorts, t-shirts, walking boots and helmet we set off for the entrance only to find it blocked by a large boulder pile. After a short discussion it turned out that this was recent and due to the explosion we had heard and the road building crew were called down to help dig it out for us. After getting promises that the blasting would stop while we were down the cave, we set off to explore and survey.

A loose boulder climb led to a hading rift which gradually became narrower and sharper with pocketed limestone. Although it looked like it would close down,we came to a T junction with a stream passage after 200 m and the cave opened up. Downstream led to a sump within 15 m so we followed the cave upstream following the streambed which meandered around boulders, mud slopes and calcite flows. A small climb led to the upstream sump with no obvious way on. On the way back we explored some of the high level passage we had ignored on the way through. The cave obviously takes a lot of water in the wet season and most of the high level we looked at involved balancing your way up greasy mud slopes pulling handholds off with each move. Nearly 300 m of old high-level passage was surveyed trending in the same general direction as the rest of the cave. In places this large dry passage was beautifully decorated with huge stal, calcite flows and clean washed black limestone.A large black pit was reached which was impassable at this stage .

Returning to the stream way we checked out a few other leads into the high level but with time pressing none were followed far or surveyed. In total we surveyed 839m and there are definitely many question marks to return to with the possibility of a major cave system yet to be discovered.Returning to the entrance we were all relieved to discover that the climb was still clear and we exited to what has to be one of the most spectacular views from a cave entrance.

Fiona Mackay

NGUOM LUONG

Having completed the main objectives we had in Cao Bang, one outstanding issue remained. We wanted to check out a sink/resurgence system noted by Carl Maxon on his 1996 visit to Cao Bang. With this in mind, we made a slight detour from the usual route to Hanoi .

Carl’s resurgence was supposedly located by a particular kilometre marker post. The area did indeed look very promisingand we soon located the specified post. The resurgence nearby proved something of a disappointment, given that it would have taken the thinnest of Yorkshire Dales thin men to pass through the tiny muddy slot. The more plump members of the team (i.e. all of us) decided that we would not let Carl forget our wasted trip in a hurry.

Meanwhile, Mr My was doing what he does best – chatting up the local women. He soon returned with tales of a real cave. Unfortunately, most of the survey gear had by this stage departed towards our next point of interest in one of the other jeeps. With a set of Suuntos, a biro and the frontispiece of someone’s paperback, plus the unused pages of Martin’s passport as backup, we went in search of measurable caverns.

Two local boys accompanied us into the cave, passing on useful tips like “No not that way, it chokes” which we studiously ignored until the passage actually did choke. A scalloped streamway was followed for a couple of hundred metres in quite a sporting fashion – especially for the boys in flip flops or bare feet! The eldest of our companions told us the streamway dropped into a muddy V-shaped passage and then became full of water. We were soon walking along the bottom in the base of the V and a final climb down led to a large inlet sump. Clearly the people around these parts are not averse to a bit of darkness!

Returning towards the entrance, the boys pointed us towards a side passage. By this stage we had no hesitation in believing them. With the only last corner of the paperback remaining, it was looking like Martin’s passport was going to get some addition which wouldn’t necessarily meet with the approval of H.M. Government! However, a climb up beyond some interesting shingle-filled phreatic tubes posed more of a problem than we wished to negotiate at this stage. Just over an hour had netted us 511m of cave (none of it original!) and a good lead remained.

The next part of the journey took us through yet more limestone scenery which gave the impression of containing plenty of cave. Travelling along by a medium sized river, we chatted away until suddenly the river disappeared. Back-tracking quickly, the reason for the disappearance became apparent – a rather large rift swallowing all the water. We were already late. It would soon be dark. The drivers would get all grumpy again. What the hell, it was far too big a lead not to check out!

A few kilometres further on, we looked back towards the valley below the sink we had just checked and were astonished to see a HUGE entrance. Expletives were duly exchanged and plans to delay departure to Quang Binh discussed. It was too late. The train tickets had been booked and paid for. The resurgence would have to wait…

Paul Ibberson

HANG KHE RHY

Hang Khe Rhy was first explored by the 1997 British Vietnamese Expedition. The entrance is located on the edge of the limestone, to the south of Hang Phong Nha. In 1997, the cave was explored and surveyed for a length of 13.8K. The main entrance called Cool for Cats after a nighttime visit by a tiger is a flood overflow. The inlet passages for the Khe Rhy and Khe Thi streams have been located inside the cave. The cave is a major river cave and forms one of the main feeders to the Phong Nha System.

In 1997 the exploration was left as time ran out, with the main river passage still wide open. The return trip this year hoped to continue the exploration towards Hang Tung, the next section of cave in the Phong Nha system.

A team of seven cavers, including Mr Nguyen Hieu of Hanoi University entered the cave for a three-night camp. The length of the cave after the last expedition meant a camp was necessary to push on downstream. The team entered the cave at midday, having walked from the nearest village of Ban Ban. The local people of Ban Ban assisted in carrying the equipment to the entrance. About five hours of caving followed, until the team had passed through Sump or Glory (a low arch at the end of a 250m swim) and 5km of passage. All the equipment had been tested for waterproofing in the river at Son Trach the day before. Not all bags were successful in the river, but thankfully underground everyone’s gear made it to camp nice and dry.

There were no obvious camping spots, so the Thousand Yard Stare was checked and found to be a dead end. Camp was eventually made on a shingle bank, with a bit of protection from the draught. After the previous expeditions, we knew we could not survive on My Thom (noodles) alone, tasty though they were, so we had brought a selection of ready meals made by Wayfarers. These proved really excellent and a good treat at the end of a hard day. The breakfasts also sustained us really well for a full day’s caving.

After an early night – an early start the next day. A team of four proceeded to take photos around camp and further downstream, and check side passages. The remaining three set off with their gear to reach the previous limit, push on and hopefully find a good camp for the second night.

The last surveyed point, What You See is What You Get, (when its 50m wide you know its going to go) was reached after traversing over a kilometre of boulder choke. The next camp therefore had to be after this. Passing ‘What You See’, the team continued for about 500m until a marvellous campsite was reached. A huge sand bank on a bend, with loads of space, well above the water, and out of the draught. A dry side passage was also seen. The team dropped their camping gear, had a brew and set off surveying. The camp was ringed with Darren drums so the following team wouldn’t miss it. A cryptic note was also left suggesting that they might prefer to catch the survey team up and push on downstream, rather than bag the nice dry side passage.

The next section of passage was almost immediately a swim of a couple of hundred metres. Many small white fish were seen here. Another low section with a howling draught and the cave opened up again. The passage continued with plenty of swimming and some bouldery sections. A couple of bends followed, and then a climb up onto a huge flowstone formation. The top of the flowstone was formed of many large mostly dry gour pools. Traversing round their narrow rims around the deep holes was like traversing around crevasses, so this was named the Mer du Glace.

Unfortunately at this point we could see daylight, which was disappointing, although it was a further 500m before we reached the entrance. The river disappeared amongst the entrance boulders. Climbing out there was lots of evidence of local people, including a hand knotted vine hanging down a 50m shaft just inside the entrance. We could see limestone cliffs in the distance, and low cloud and rain. The team made a brief reconnaissance but realised they didn’t have time to achieve much, and so returned. An additional 1.9km had been surveyed. Back at camp, the photo team had bagged the dry side passage, as they didn’t have time to catch the survey team, hence Disobedience Passage. A good night was passed at the camp,” The Good the Bad and the Vodka” with more nourishing food to accompany the alcohol.

The next day, the bad, set off for the exit, Huda Thought It, to try and find out where it was and if there was any continuation. The good set off to survey a side passage, which seemed to be going, arranging to meet up with the vodka back at camp one.

Reaching the exit, the team followed a path, which led to another huge entrance. Meeting up with some woodcutters, Hieu was able to ask them for information. It seemed this was Hang En, a short section of cave, which had been explored in 1994. Unfortunately this meant the exploration was probably finished in this area, as downstream had been checked out and found to be a massive impenetrable logjam. The combined water of Hang Khe Rhy and Hang En joins at this point to form the full Phong Nha water.

The survey team continued to Mendip Head passage, a smaller than average side passage. Initially a gour slope, the passage developed into a mud floored abandoned streamway. Easy going apart from the mud, the team was surprised to see their team-mates footprints continuing after several hundred metres. The motto for caving in Vietnam is no pushing without surveying!

After a second acute bend, the passage opened into a breakdown chamber with fine formations. The way on continued over slabs and into a smaller section of passage, finally leading to a crawl over mud and then boulders. Determined to make the most of what could be the last trip into Khe Rhy, the virtuous survey team pushed this uninviting lead. The reward was to emerge into larger passage, which soon dropped into a large abandoned passage going both ways.

Yorkshire Way was followed in the ‘downstream’ direction first. This is a very old passage, with remnants of gour dams and very sharp water worn limestone. Disappointingly after 200 metres the passage ended in a huge collapse chamber. There was no obvious way to proceed, and the climbing options looked too risky.

Returning to the T junction, the team surveyed ‘upstream’, initially a fine passage with gour floors, the roof soon lowered leading to stooping but thankfully no crawling. After about 400 metres, the passage ended at a small pool surrounded by formations. A calcite blockage stopped further progress.

Once the survey was drawn up, it was obvious that the two ends of Yorkshire Way are very close to the edge of the limestone, with no further potential. Tired but with a good days surveying (another 2km) the team continued to camp.

Returning from their excursion to the outside world, the others announced that it was raining, but had been doing so every evening since we’d entered the cave. Since we had not seen any increase in the water so far, we felt safe in camping and exiting the next day. Tiredness, hot coffee and dry clothes also contributed to the decision. The next morning the water had risen a few inches, but this presented no problem, and the team made a safe exit.

The total length of Hang Khe Rhy now stands at 18,902 metres, the longest cave in Vietnam. The water from the Hang Khe Tien entrance is not seen in Khe Rhy, and must join the system via a separate route. There is potential for 3-4km of cave from this entrance. This brings the total surveyed length of the Phong Nha System to 40km.

TRUNG HOA – MUCH ADO ABOUT SUMPING

After meeting the Snablet and Simon in Hanoi, the group had travelled south by train to Bo Trach, where a meeting and lunch was held with the People’s Committee, the key interest at the time was the potential for World Heritage Site status which was being investigated for the Ke Bang massif.Our goals were threefold, primarily to complete the investigation of the Khe Rhy river system, secondly to explore a large area of sinks to the north of the main Chay river resurgences and finally to examine several leads in the central area of the massif, either side of Highway 15(the Ho Chi Minh trail).

On arrival in Son Trach, and after a visit to Hang Phong Nha accompanied by a film crew, a short investigation was made up into the scrub above Phong Nha yielding the cave now known as Phong Nha Kho (qv).The team then split into two, with Mr Phai, Howard Limbert, Anette Becher, Pete O’Neil and Simon Davies intending to travel Highway 15a towards Minh Hoa which was the previous limit of exploration some years earlier.The road was now reportedly easier to travel and could be passed using a 4wd as opposed to the seemingly ubiquitous Russian and Chinese 6wd military vehicles.

Our goal was to head round the top of the massif by vehicle and venture into its interior on foot to examine the sinks and watercourses.

The next morning we chortled as the other team’s transport arrived to take them to Ban Ban; the journey from previous experience was going to be tough and unpleasant and we awaited for our promised vehicle to arrive. Of course we thought, they’d have to move that dilapidated old bin lorry first.Our humour came crashing down to earth as we realised that this was the transport which awaited.What followed can only be described as hurried re-negotiation; Howard was doing his level best to convince the owner to go away and get us something decent- a land cruiser perhaps?

Eventually a Nissan 4wd with a nice big V8 and air conditioning arrived.The truck seemed perfect, other than the size.It was immediately apparent that with the a total seating capacity of 4 (if you are small or a contortionist) and 5 team members, plus the driver and his mate, that things could be a little uncomfortable and that sooner or later someone would have to go in the pick up part of the truck.This area was a hard top with nailed shut windows and a propensity to effectively distil the carbon monoxide straight from the exhaust and pipe it directly to the pick up area.

To make matters worse, the temperature was climbing fast as the recent cloudy spell had given way to bright hot sunshine.We decided to load the gear in such a way as to make it moderately comfortable in the back and induce team members into the sauna with a hastily purchased case of beer.We set sail for Son Chay, the first sink we wanted to examine, this was about 2 hours driving but it was two hours in the very jaws of Hades itself.Sitting in the back part of the jeep was nightmarish, the temperature was stifling (at least 40C) with no air whatsoever, opening the tailgate let in fumes and dust, so we decided to take turns.It also became speedily apparent, that our driver was perhaps unsuited to his job as a driver.As soon as the vehicle got moving, he changed straight to 5th and relied on the grunt of the V8 to pull us along while the engine laboured.

On arrival at Son Chay(past the old airfield, 3rd on the left) we disembarked and went cave hunting, a short walk across some neatly cultivated land in very hot sun took us to the end of the valley where the river sank.There was much scrabbling around some boulder collapses, however the river clearly disappeared into a boulder ruckle.Since all the cave in the area had previously been very large, it was felt that to pursue this may not be as fruitful as looking further along the edge of the massif.

After a short discussion with some locals over a cup of green tea, it transpired that they knew of no caves in the area.We pushed on back to the truck to head over the pass on the highway.The highway gradually deteriorated from being a dirt track to some ruts and stones through the jungle.The pass on Highway 15a follows the northern edge of the massif until it crosses some low sandstone hills to the north, the apex of the pass then leads down into now familiar karst geo-morphology common around the edge of the massif, namely spectacular tower karst.After a few hours of this we came upon a small village with an army checkpoint, again the procedure was simple.To find cave in the area, ask the locals, particularly the elders, as many of the caves were strategic in the Vietnam War as staging posts, defendable sites and bunkers from the bombing raids.Talking to the villagers an elderly man claimed knowledge of a cave, not far away – he could walk there, the man grabbed essential kit, torch and pith helmet, and trotted off down the road without waiting to see if we were following.

Further conversation with army officials revealed to us that there was indeed a cave in the area but it was in an area closed to all personnel and that in any case there were bigger caves further down the valley.Heartened by this news we headed off down the improving road.As we crossed into a low valley with extensive cultivation a large river was spotted.A moment’s deduction led to Pete and Anette skipping off into the undergrowth to look for the source of the river.A large entrance was discovered with a significant amount of water emerging over rocks spewing from an entrance lake.Pete quickly stripped off and swam out to an almost immediate sump.This was confusing; sumps are rarely seen in the massif with only one or two noted. Worse was the water direction, it was flowing away from the Chay resurgence towards Minh Hoa. We pushed on into the nearest town and reported to the army base.

We took tea with the base commander and his assistant (not sure of either rank, but lots of stars and stripes) and were immediately offered a wing of the garrison to use as a base for our explorations.We moved in and prepared our evening meal while eagerly looking at maps for the next excursion.

We intended to climb over the ridge into the cultivated area and examine the two particular water courses which seemed to be a perfect site for a cave.Local knowledge provided us with useful information, the walk over the ridge would not take long, and that there would be a small village on the other side with plenty of paths since this was a main route over into Laos (hence the border post as the town was the first to be arrived if travelling from Laos ).

We set off early the next morning hoping to break the back of the walk before the weather got too hot.We crossed into the village over a small suspension bridge and set about clambering our way past the reservoir over the tower karst.It was amazingly pleasant, no leeches, shady and after a short climb a wonderful plateau with tall trees and leaf litter floor.After a little of this, there was a small stream to cross which was emerging from a pile of boulders, unable to pass the opportunity by, we had a quick paddle to examine the resurgence and declared it a dead end, though the water was icy cold and very clear. Again bizarrely we were up on a limestone plateau and here was a spring.The hydrology was beginning to look a little weird.

On arriving in the village we spoke to the headman for a while and took a bowl of tea and discussed the rivers in the valley and the cave.It was a little disappointing, when we got to the first river which we were expecting to flow from right to left – i.e. in the direction of the Chay resurgence but the thing was flowing the wrong way!The local confirmed that there was no cave at the end of the river but there were a few caves over near Laos some 2 days walk away.We asked about the other river which joined a few hours down stream and asked about the source of this.The man kindly offered to show us the way.We decided that since a good part of the day was gone, to dump unnecessary clobber and head lightweight into the bush. If we had any luck we could return.

The weather was now red hot and it was extremely hot and tiring work keeping up with our newfound friend.At some stage he asked if we were part of the expedition, we answered “what expedition?” The answer came an hour later as we stumbled across a group of low makeshift tents by a bend in the river, populated with Russians.Both sides were amazed and quite pleased to meet and a quick cup of tea ensued.The Russians were entomologists looking at butterflies and insect species; they were also interested in Bats.Bats equals caves and the discussion got interesting.The whole area had been searched for bat roosts (caves especially) without any luck which disappointed us all.

We turned round with a resigned “call it a day” atmosphere descending.

That evening a small cave near the military base was explored which unfortunately did not lead anywhere and contained no running water.After a good night’s kip we rose early and struck out across the flood plain that was opposite the army base. On our way over to the river crossing anenterprising young fellow on a bike was honking a horn and bellowing, we joked that he was selling ice cream out of the big box on the back of his bike.Strangely this was exactly what he was selling, at 300 dong a piece we attacked the chap’s supplies like starving beasts.Refreshed and a little surprised (well he had cycled 60km with the stuff) we pushed on, a promising looking hole was investigated and unfortunately ruled out.We moved to the other side of the valley where a strong draft was found, it was cold and hence promising.We furtled around boulders with no discernable draft and came to the conclusion that it was probably katabatic downdraft caused by the cold air sinking down the tower karst. – there was certainly no sign of any cave !.

Disheartened we made our way back in the searing heat to the army base.An experience only lifted by discovery of a rather nice swimming pool crafted out of a dammed river.It was now time to move on, this was expedited and we headed to the next town.We made our rapid way to the local party official who after a few cups of tea pointed out that the area had already been looked at and the only large cave in the area was Ruc Mon which was explored by the 1992.Thoroughly pissed off we decided to go back to Son Trach and make some forays from that part of the countryside.It was clear that this area was not going to yield the desired results.

Simon Davies

HANG PHONG NHA KHO

As soon as we arrived in Son Trach we were told that a dry cave had been discovered approximately 100 metres above the entrance of the area’s main tourist attraction ‘Phong Nha’ show cave.

The officials from Quang Binh and Son Trach were interested in the potential for extending their show cave business by incorporating the dry cave into the tourist experience.To this end, before our arrival, a track had been cut up the very steep hillside above Phong Nha river cave.

The possibility of high level development could not be ruled out, so half expecting a short cave cum alcove a team consisting of Mick, Martin, Huey and Snablet was sent for a look.They surveyed approximately 400 metres of old large dry passage to a 10 metre pitch, all of which had been entered before by locals.

On the follow up trip Simon, Howard, Anette, Phai and Pete dropped the pitch and surveyed along a 20 metre wide flat sandy floored passage. This section of passage was virgin and before us stood two superb stalagmites shaped like cobras in a dance.The dimensions increased to 30 metres by 20 metres the sandy floor being the only obstacle.Very old stal and flowstone decorated this excellent passage, until after nearly a kilometre we entered a large chamber some 40 metres wide and 20 metres high.We searched for some time but no way on could be found; all leads were either choked with calcite or breakdown, so we called it a day and headed out.

As we neared the entrance it become clear that it was raining heavily outside as small stream now flowed in the previously dry passage.The cut path down to the river cave became treacherous in the wet as we surveyed down to link the two entrances.

The dry cave is a quality section of cave passage and hopefully the Vietnamese as they develop the cave will be ever thoughtful of just how fragile this environment is.