Only a thousand people have passed through this cave since its discovery. We were lucky enough to be among them.

It was 1991. A Vietnamese logger named Ho Khanh was hiking through the jungle near his home in Phong Nha, in central Vietnam. Drawn by the sound of rushing water, he came to an opening in a cliff. A strong wind blew clouds out of the cave—an intimidating site, and enough to keep Ho Khanh from searching deeper—so he turned around and went about his business. That was the unceremonious discovery of Sơn Đoòng, the largest cave in the world. “It’s five miles long, 650 feet high, and 500 feet wide,” writes Ken Jennings for Traveler. “It could hold an entire city block of Manhattan, including 40-story skyscrapers.”

And somehow, it managed to remain a secret for centuries. But by 2005, the surrounding area had become something of a destination for spelunkers, and Ho Khanh realized he might have been on to something. It took three years of searching, of tracing his steps, before he was able to find the opening again, but when he did in 2009 with a British caving expedition, they became the first people to tackle Sơn Đoòng. Only a thousand or so people have done it since—including us. This is our five-day trek into the center of the earth.

About two hours in, we stopped by the village of Ban Doong for lunch, en route to the first night’s stay in Hang En cave. It felt like we were passing through another time, long since forgotten by the modern world.

Our first day had been a wakeup call. Sure, we had hiked a bit before—Table Mountain in Cape Town, a trek in the Adirondacks and such—and who hasn’t done a spot of camping over the years? But that was nothing compared to the Sơn Đoòng trek, full of hiking in the sweltering heat and humidity of the Vietnamese jungle and the relative chill, but still humid, cave interior. Then there was the technical climbing, waist-deep river crossings, and scrambling over rocks that were often steep or sharp or wet—or all three. We were quickly becoming aware of just how intense a journey this would be—and equally aware that it was worth every ounce of effort.

Sam sets up the large-format camera for one last shot before leaving Hang En.

The path wasn’t direct, the terrain wasn’t flat. It was starting to seem like a miracle Ho Khanh had ever found this place. We didn’t even notice the cave’s entrance until one of our guides, Vương, pointed it out. At the bottom of a large cliff face and almost obscured by jungle, it certainly gave no real indication of the scale that lay within. As we got closer we became aware of another reason it was only partially visual: From our vantage point, it was straight across from us, but in reality that was just the top of the opening. While the entrance to Hang En has been a walk across a flat beach, the way into Sơn Đoòng was a steep descent over wet, mossy rocks.

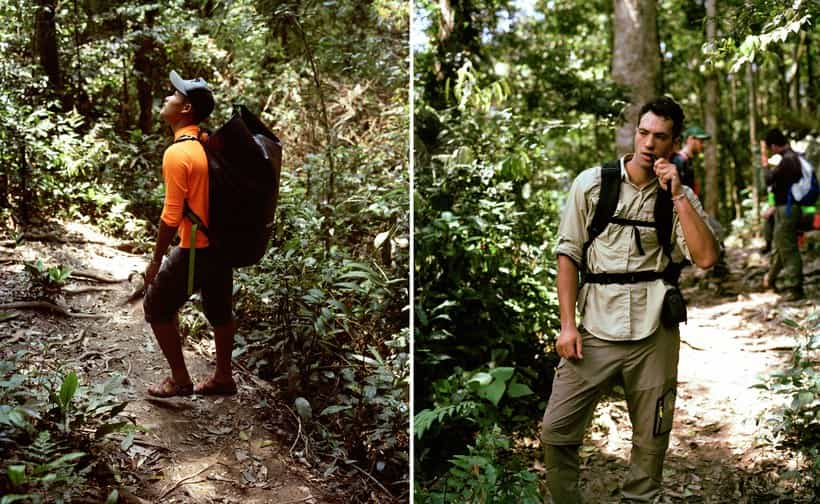

Helmets and gloves on, we climbed down. And climbing it truly was—clipped into ropes, and with the constant aid, advice, and encouragement from our guides. Led by Adam Spillane, one of the original team to explore Sơn Đoòng, and Ian “Wato” Watson, a U.K. caving expert, we were always in good hands. They were always friendly and helpful, and very aware of the situation at hand. Along with Vương, the head Vietnamese guide, and the rest of the cavers, we were carefully looked after without ever feeling coddled.

Photos can only begin to express the otherworldly atmosphere, a mix of landscape and fog and light.

Slowly, with the daylight behind us, we made out way into the depths. As we reached the bottom and carried on a bit farther we reached our second camp site. In the amount of time we had taken to get there, the porters had packed up the old site, beaten us to the new, and gotten everything set in the Sơn Đoòng location.

And that location was beyond belief: a small, flat plateau in a huge cavern of rocks and boulders. In the distance, across a large chasm, was the failing light of the opening far above. Actual clouds hung inside the cave—Sơn Đoòng is so large, it has its own weather system.

It’d be easy to think this is a cave entrance at a glance. It’s actually the beginning of an opening under a doline. Sơn Đoòng has two large dolines—sinkholes that have collapsed some 300,000 years ago to create giant skylights in the cave. The light, wind, and rain have, over time, allowed an entire ecosystem to develop.

This was our world for the next three days. There’s something truly surreal about waking up in the cave. The environment was as entirely alien—amplified by the complete lack of natural light. All sense of time and scale are lost. We would walk through narrow corridors and emerge in underground chambers that seemed the stuff of fiction—the terror of Ridley Scott’s Alien as much as the envy of Tolkien’s dwarves.

That was norm of the cave: hiking and climbing to see the most amazing thing you’ve ever set eyes on, then doing it again, finding something even more amazing. It never ceased to outdo itself. Giant chambers of rock with stalagmites and stalactites were like giant, groaning jaws. (Sam takes a photo with the Pentax atop a stalagmite here.) We walked though a jungle actually inside a cave and over boulders the size of buildings.

We swam in a narrow chasm filled with the most crystal-clear water.

One doline in particular is so large, the light pouring in, you might think you’ve exited the cave into some prehistoric jungle; it’s aptly named “Watch Out for Dinosaurs.” This is one of the most breathtaking views within Son Doong. We were incredibly fortunate to catch it on a rare day when the weather and light combined to form this sight.

Approaching the second doline involved a steep climb, scrambling over boulders—but that was nothing compared to the 262-foot-tall Great Wall of Vietnam. By far the most physically difficult part of the journey, it was the last hurdle before getting out of the cave.

The first part was “easy”: climbing a 50-foot ladder with harness and carabiners. The second part, the ascent at its steepest, was nearly vertical. Feet are merely anchor points and your arms pull most of your weight. Honestly, it’s still hard to believe we managed it. Finally, the last third: still steep, but a cake walk after the vert. And we’d made it.

We made our way toward the light and our exit point, legs like Jello. Looking back, we appreciate even more how great the Oxalis team was. Most of us had little to no real experience in conditions this extreme, but our guides, poised and smiling, got a group of ten random people through the largest cave in the world. We were an unlikely band of travelers: a restaurateur from Hawaii, an IT guy from San Francisco, a software engineer from Zurich, a dry wall contractor from Melbourne, an ad agency owner Ho Chi Minh. We each had our reasons for being there, but we had a common goal: to experience the natural wonder of Sơn Đoòng.

From CNTraveller